Racism & the ISL student body

June 20, 2020

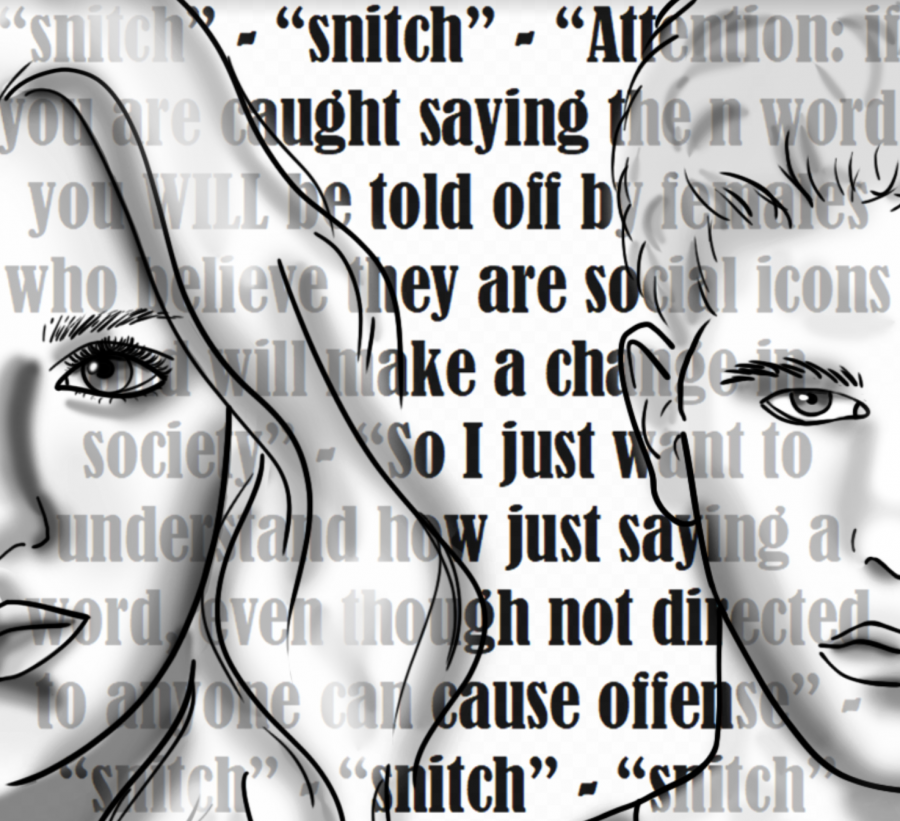

On June 1st 2020, I posted a series of slides on Instagram with the title: “A Collection of Racist Things I Have Witnessed at my Institution.” In it, I condemned the toxic environment created by the student body, where people who speak up are ostracized by their peers. I also put the racist actions I had seen at this school front and centre, laying it to my peers in (literally) black and white, and I urged my fellow students to, collectively, reflect on the ways in which they themselves have been complicit in perpetuating our school’s racist environment.

The response, for the most part, was overwhelmingly positive. The post served as a way for the once silent bystanders to speak up against the rampant racism present in our institution, which is often brushed off as “banter”. It was effective, at least temporarily.

This post revealed a lot about student mentalities regarding racism. There was a hesitation among many of the more privileged people at our institution to accept the fact that in many ways, our student body is racist, and that this racism is hindering the day-to-day lives of many black and students of colour at our school.

Most notably, one boy managed to invalidate our experiences as students of colour. In a lengthy (now deleted) comment, he told a black student that “if you compare the labels of racism in our school, and I am not saying we are void of it, to other schools, it’s completely different. We’re not to the point where it’s an alarming level, no one’s education is being affected by statements around them… Our school scrapes the bottom of the barrel in terms of racism compared to the shit that’s happening worldwide, especially at other schools. We are just privilaged [sic.] and it’s blinded you to some extent, as students of color in different schools experienced far worse conditions than those at ISL.”

Before deconstructing his statement, it is important to look at the power dynamics involved. There seems to be a lack of understanding on his part: as a white student, he cannot tell a black female that the unbridled racism at our institution isn’t hindering her education as he will never know what it is like to be a black female in this world today. While his voice was a singular one, his opinion seemed to resonate with other members of the ISL community.

In the comment, he makes the argument that privilege lessens the blow of racism. In a sense he is correct, as tensions among races are heightened in poorer communities where violence is an incentive. An example of this was the 1991 Mt. Pleasant race riots in Washington, DC where racial tensions among the working-class Latinx and Black communities escalated after a Salvadoran man was killed by a black police officer (for those interested, this is discussed further in this journal article).

However, racism still penetrates class barriers. A perfect example of this is the now viral video of the NYC dog-walking lady: after a black birdwatcher politely tells a white woman to keep her dog on a leash in an area where it is mandatory, she threatens to call the cops on him. Like many of our parents, both people involved in the incident were highly educated (the birdwatcher being a Harvard graduate and the lady being a UChicago graduate) with high-paying jobs (an editor at Marvel vs an investment banker). At the end of the day, a Black man walking down the street is still a Black man walking down the street, even if he was educated at an Ivy League institution and has a high-paying job.

This student’s statement demonstrates that, as a collective, we have missed the mark on race education as a whole, and in two main areas.

Firstly, our race education has distanced us from the everyday realities of racism. It might be true that we were taught about segregation, the Klu Klux Klan, the death of Emmett Till, and the civil rights movement, but we have never learnt about the systemic racism shackling down many people of colour today. As sociologist Eduardo Bonilla-Silva puts it, “the main problem nowadays is not the folks with the hoods, but the folks dressed in suits.” Additionally, we only learnt about racism in the context of the US for a brief period of time: for around two weeks in Year 10. Race education needs to be discussed continuously and in every subject, in order to gain a broader understanding of the issue. The need is amplified even further when considering that we are a school where many students move countries from year to year and have not had the same educational background.

Secondly, we have not had any form of diversity training as students. Studies have shown that this improves cultural understanding and empathy among students. For an “international school”, it is surprising that we don’t have something as simple as a yearly, student-led session where we are made to deconstruct the ways in which our many individual privileges and implicit biases shape our understanding.

The school administration has understood the need for these two elements to be implemented into the curriculum, which is a sign of progress; however, as students, we also have a responsibility to make our environment a more unbigoted one. It is upon ourselves to abolish the existing mentality wherein students who speak up are ostracized. As a student body, we need to foster a community of activists as opposed to a community of silent people. To go back to the Instagram comment, even though “racism might be worse at other schools”, that doesn’t mean we don’t have to take action to dismantle racism at our own school first.