Solving the Equation: Women in STEM

Let’s close the gap.

In my math class a few years ago, we were asked to name any five mathematicians in history. Students jumped away at the task, yelling out whatever answers came to mind: “Pythagoras!” “Euclid!” “Fermat!” “Ramanujan!”

But when we were stopped and asked to name any one female mathematician, the class went silent.

Women make up only 28% of the workforce in science, technology, engineering and math (STEM), and men vastly outnumber women majoring in most STEM fields at college. The gender gaps are particularly high in some of the fastest-growing and highest-paid jobs of the future, like computer science and engineering. In Switzerland, gender segregation is extremely noticeable in universities of applied science, with only 21.3% of students in STEM courses being female in the academic year 2017–2018.

It’s important to point out here that some STEM fields are more strongly gender segregated than others- for example, the lowest proportions of women are in technology (8.5%) and informatics (10.4%), whereas in chemistry and life-sciences the numbers are higher (43.7%).

And on top of that, these numbers are increasing slower than ever, if not reaching the peak of their growth.

But the problem doesn’t lie in job applications, college decisions, or even attending courses in the DP. It starts at a much younger age: primary school. Try asking reception to year 5 students to draw a scientist. A study in 1983 showed that only 28 female scientists were drawn out of 4,807.

Is 1983 too old?

In a 1995 study among students of 9–12 years of age, there were only 72 pictures of a female scientist out of 223, and of those 72, only 13 pictures were drawn by male students. In 2018, the general image of a scientist still remains as an elderly man in spectacles and a lab coat, who may wear a beard or have unkempt hair…

Girls should in no way be forced to pursue STEM later on in life. If it’s not their interest, then it just isn’t. But many of them aren’t looking to see if they are interested in STEM in the first place.

At ISL in 2018-19, the gender breakup for ASAs such as computer science and math enrichment remained as 27-9 and 13-6 for boys to girls.

Okay, well, why do we need more girls in STEM?

Creativity stems from men and women alike- and the answer’s just so simple. Women can provide so much innovation to each industry; they generate jobs and can use their creativity and voice to re-engineer the world into what it can be with them in it.

According to a McKinsey Global Institute report, increasing women in STEM fields can equate to an additional $12 trillion in the global GMP.

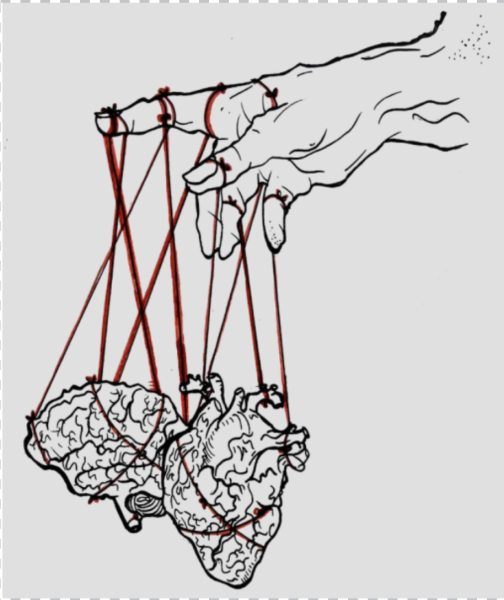

It’s often said that a lack of female role models deflates the interest for STEM among young girls. Stereotyping and troubling social norms are also culprits of discouraging girls from STEM.

“In most schools you see in the movies, the ‘cool kids’ are often the ones who are not so smart. It’s always the captain of the football team who’s flunked maths 6 times and that’s what movies portray,” remarked Ms Harrison. Girls in middle school who are trying to shape their identities are swayed away from what seems boring, difficult, or generally ‘not cool’.

STEM subjects from the get-go are being portrayed as these, and therefore appear unattractive.

In truth, it’s not that we don’t have what we need to show girls the beauty of STEM. We have many role models- we’re just not trying hard enough to look at them.

Every female teacher at ISL in STEM who has encouraged girls in the same way as she has boys to graph a quadratic function or balance a chemical equation is a role model. Every male teacher who’s pushed girls to create a running python program, or design sustainable architecture is one too. Every female ISL student who’s worked hard to tackle Physics or Chemistry is the best steminist of our time.

And in truth, being a girl in STEM is cool. It’s really cool. Something as simple as joining the coding ASA, taking part in a maths competition, or spending a few minutes to read the Women in STEM posters as you pass by them in the ISL hallways makes you realize just how amazing it can be.

Breaking stereotypes requires at least one person to step out of their comfort zone. And stepping out doesn’t have to be girls forcing themselves to swallow math problem after problem, dedicating themselves to nothing else. Why can’t they be more than that?

“We need to really find the captain of the football team who’s taking higher level math,” Ms Harrison continued, “to really highlight those girls who are not just predominantly seen as the girls who are going to do well in maths, but that she can do both!”

So girls. Take time in class to ask your teacher an extra question about cells. Look into how to make a drone fly, or code a program to play chess. Design an ergonomic chair, create AI that sorts plastic waste, and when you find a math problem difficult, try again until you get it. And enjoy it.

As Ms Rudd puts it: “Study what you enjoy, not what you think you should do. Dare to be different and be curious about the world around you.”

I hope one day, a few years along the line, when an ISL math class is asked to name a female mathematician, a young girl will put her hand up from the back of the classroom. And she’ll hold the future in her eyes and be able to name them all.

I’m a year 13 student who loves chemistry and poetry! I love writing about STEM, and I’m looking forward to writing more opinion articles and current...

Dorka Borus • Feb 5, 2021 at 12:25

I think that this article was very nice, it gave me a lot of perspective about gender gaps in the world.