Through the Looking Class

International schools are a paradox of sorts. On the one hand, from their conception, they have been seen as an idealistic means to promote interdependence among communities and celebrate diversity in all of its forms. On the other hand, international schools have always existed to educate an elite group of students. The first international school—the International School of Geneva—was created to serve the children of employees of the League of Nations and the International Labour Office.

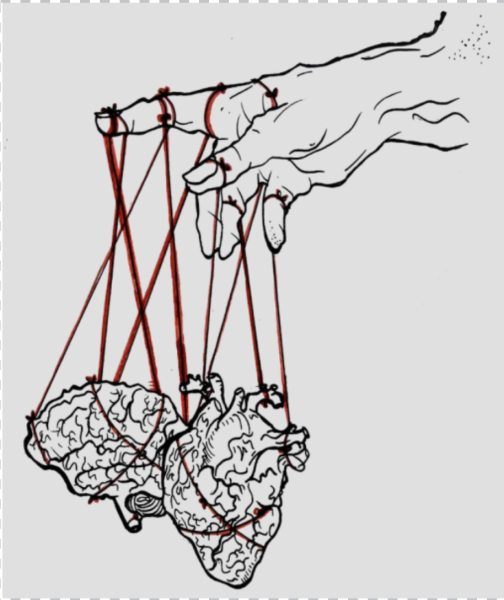

This “international school paradox” has created a culture of contradictions, an environment where students are taught to be “global citizens” while at the same time having limited expertise regarding issues affecting their local communities. An environment where students are taught about the importance of equity while attending a school with a fee of CHF 33,000 a year. It is this distinct culture that creates the “international school bubble”.

The ISL bubble is an interesting one. It embodies all the aspects of the “international school bubble” while boasting about having a strong and diverse community. The statements do not specify what exactly this community is, but they use possessive pronouns when referring to it: “our community”. Does this community involve the local Le Mont community, or have we partitioned ourselves from the commune that our school has been a part of for the last 15 years?

I asked a randomly selected group of students (who have lived here for more than three years) in an anonymous survey if they feel like they are a part of general Swiss society. The responses were striking: “I often feel a bit alienated or separated from the broader community,” wrote one student. “I speak French, have adapted to their customs, and know about Swiss traditions and such. But most of this was because I tried to integrate myself into it; if anything being in ISL slowed the process down,” wrote another.

Integration with the local community does not seem like ISL’s immediate priority. But it should be. It is about time we burst the ISL bubble.

Some international school students have a difficult time “fitting in” even if they have spent all our life in their country. A student mentioned that they don’t feel like they belong because “there is a huge language and cultural barrier that ISL doesn’t really help us break.” Having a sense of belonging with the area we live with is immensely important as it could help widen our perspective and become better learners. Some people, however, are used to living in this bubble and are content with living within it.

Furthermore, integrating with the local community allows for increased awareness of regional political issues. There is an alarming lack of awareness when it comes to Swiss politics—many ISL students would blank out when asked who the Swiss president is, or what some of the upcoming referendums are. Swiss politics affects all of us, regardless of our nationality. Some parties are even trying to put forward legislation allowing non-citizens to vote on certain issues.

Most importantly, ISL prides itself on its “diverse” community. This surface-level diversity will only take us so far as an institution. We are encouraged to embrace the perspectives of our peers and actively seek out a diversity of opinions. When doing this, it is inevitable that we hit a roadblock: seeking out diverse opinions from a group of mostly white, liberal, upper-class students can be challenging. We might have over 75 nationalities represented at our school, but we only have two classes: middle and upper. For the students who answered my survey, this was a frustrating truth: “I think the major area ISL lacks in diversity is in terms of class. I know this is expected because it’s a private school, but then I think the school shouldn’t preach that our school is so diverse and the students are so exposed when it really just isn’t the case.”

Allowing for more socioeconomic integration will ultimately improve ISL’s real diversity, which is something we have been trying to achieve for years as an institution. Conversations about race, for example, are only really productive when we consider various class barriers. A Swiss government study states that: “households with a migration background have a lower disposable household equivalent income and less wealth.” These backgrounds include countries such as Sri Lanka and Eritrea—nationalities which could use more representation at ISL.

With this being said, there are ways to improve this.

All new students should spend some time fully immersing themselves in Swiss culture, whether this is through local clubs, service organisations, or sports teams. ISL should help facilitate the links between these organisations and students. Students who did feel like a part of the local community mentioned that joining outside clubs was partly the reason behind this. We also need to rethink the way we look at service-learning – we must prioritise engagement with local communities over working with external organisations abroad.

Furthermore, ISL needs to embrace its local community by using the resources available to us. One such example is the ISL garden—opening up opportunities for local gardening enthusiasts to aid in the development of this garden can help strengthen the bond between the local and ISL community.

Superficial means of bolstering our connections with the local community through advertising can only go so far—we continue to solidify our image of a slick-looking school full of “global citizens” who are out of touch with the community that many of us live in.

I’m Tanvi, Editor-in-Chief of The High. I’m The High’s resident pretentious music snob™, which is a title that I take very seriously. When...