Artificial Unintelligence

I’ve always been told, “The data does not lie.” However, for me that has never been the case. The data nearly always lies.

It was in Year 8 when I first got to experience the wonders of machine learning in AI, when my teacher helped me put together a facial recognition program as a mock security system.

When the code was finally ready, I sat right in front of the camera for 30 minutes wondering why the software wasn’t detecting my face. But when I turned my computer over to my friends, a green square lit up around their heads. The program worked perfectly. I realised: it just didn’t work for me.

In our technologically advancing world, we are falling behind. Google Image search results for “healthy skin” show only fair-skinned women, and “Black girls” still returns pornography. AI databases disproportionately assign labels such as “failure”, “drug addict” and “criminal” to dark skinned faces, but data sets for detecting skin cancer are missing samples of darker skin types.

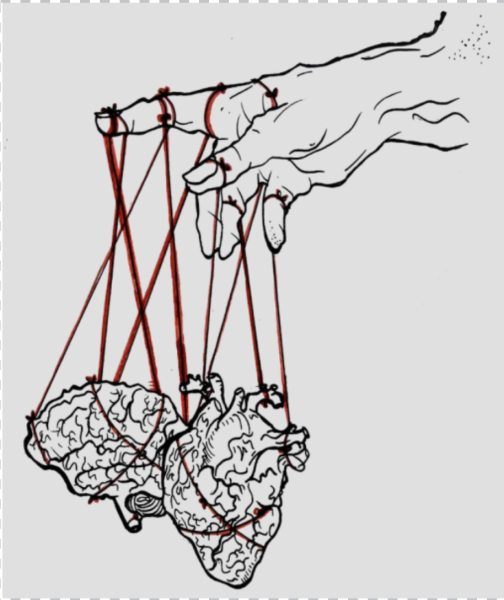

White supremacy often appears violently, in gunshots at a church or sharp insults thrown at victims in public- but it sometimes takes a more subtle form. Data sets, however diligently procured, are a representation of human choices influenced by all of our biases from the past. Data on crime, for example, is derived from the choices patrol officers make on which neighbourhoods to monitor and who to arrest. And as a result, machine learning is just a seemingly more reliable manifestation of the centuries and centuries of prejudice humans have failed to erase.

Because what is the difference between the patrol officer who overpolices minority areas and the algorithm that sends them there? What is the difference between a discriminatory doctor and a program that denies you a hospital bed? A segregated school system and a discriminatory grading algorithm?

Technology isn’t independent of us and our bias; we have created it and have full control over it. It is impossible to determine just how widespread AI is in today’s world. As it increases in relevance, biased data spreads too. It is seen when face ID on a smartphone tells an east Asian person to “open their eyes” or airport security databases target people of colour.

The answer is straightforward, but by no means an easy task: we need to stop presenting this distorted data as truth. There is no such truth in a world where algorithms systematically exclude POC from jobs or where self-driving cars could be more likely to hit pedestrians with darker skin. The truth we need to start fighting for requires conscious change. If we want to teach machines how to recognize our faces, we have to teach them to recognize all faces. If we want AI to work, we have to make it work for everyone. In the effort to fix our technology, this truth will unveil itself.

Our data will only stop lying when we do.

I’m a year 13 student who loves chemistry and poetry! I love writing about STEM, and I’m looking forward to writing more opinion articles and current...

I’m a 16 year old student in ISL. I've been in ISL for 8 years. I work on the illustrations for articles (specifically the horoscopes column) and a podcast,...