Unashamedly Masculine

This is what masculinity looks like at ISL

Born in 1957, I didn’t fit into the parameters of traditional masculinity. My best friend until the age of 11 was a girl, I had no interest in football, and I loved music and drama and imaginative games starring the dolls in her doll’s house.

At age 11, I went to an all boys, selective school – and this was initially a shock. I had to learn the rules quickly, yes. And although our sexuality was closely policed (there were no gay boys in my school in the 1960s and 70s haha! – male gay sex was a criminal offence until 1967), other gender norms were ironically more flexible without the presence of girls (and I’m not advocating single-sex education here).

In my first week of high school, I found myself on the First 11 field hockey team. When I questioned the master (what we called our teachers back then) why, he said “You’re an Ivett.” My older brother had been at the school and had played county cricket and hockey – and, of course, ball skills run in the blood. I sadly had to disabuse my teacher and unashamedly follow my own agenda: drama club, poetry society, chapel choir, school orchestra, and school magazine. Yes, sports had high kudos but masculinity was more nuanced – and I found I could be myself, express my individuality, and still feel confident in my masculinity. Was this because we were all boys and had less to prove – I don’t know?

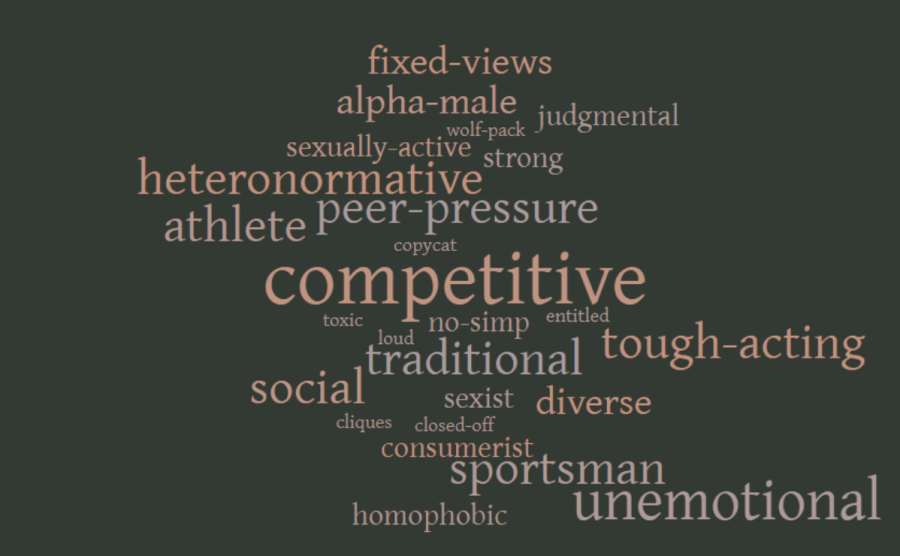

So what does masculinity look and feel like here at ISL? Last term, I asked my Year 12 class to choose five words that describe masculinity in their year group. We wrote them all on the whiteboard and numbered the duplicates before making a word cloud:

My heart sank as I noticed how little had changed from my days at school and how some boundaries even seemed stronger, particularly the tough-acting competitiveness and the absence of emotional expression. We talked about how performing masculinity daily within these boundaries must be hard work and exhausting, leaving boys feeling vulnerable and exposed if they don’t make the grade. We talked about the effect of this on the mental health of our boys, particularly if you can’t express your feelings without being perceived as sus or simp (yes, I learn new words in English class, too). Of course, you can always opt out completely and sit on the margins – in a sort of gender apartheid, I guess.

I recently read “This is how it always is” – a novel about a child negotiating their gender identity. After living four years as Poppy, a girl with a penis (which none of her friends are aware of), she is “outed” by two classmates at the end of primary school. In the heart-rending climax, she tells her high school brother that she has no option but to go back to living as a boy, Claude (her birth name). But, equally painful for me to read, was her brother’s heartfelt warning about how difficult living as a boy can be:

“Guys get beat up for asking how you are. Caring how you are. Using long words. Pronouncing them correctly. Wearing colourful clothes. And that’s just the beginning. If you’re too smart, too dumb, too cool, too worried about being cool, too nicely dressed, not hiply enough dressed, listening to the wrong music, listening to the right music on the wrong device, asking stupid questions in class, asking smart questions in class, asking questions in class that lead to more work in class, slow in gym, nice to a little kid, nice to a teacher, nice to your mom in the school grounds, too good with computers, too often reading, caught watching a movie with subtitles, if you’re a guy, someone’s going to beat you up.”

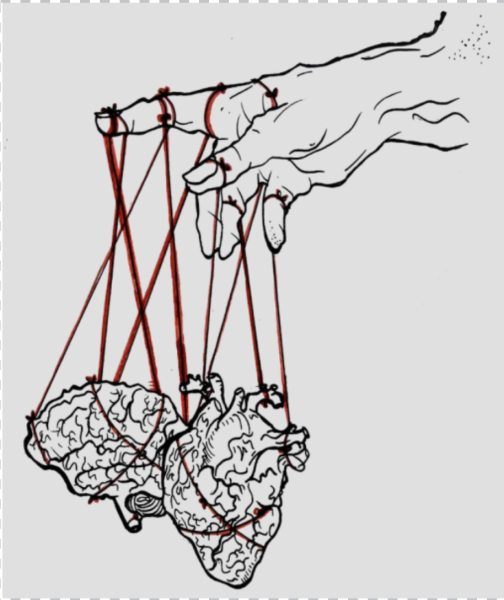

Poppy’s brother is right – masculinity is the armour, a form of school uniform, that many of our boys put on each morning to avoid being metaphorically (and maybe in other schools, physically) beaten up. But armour comes with its downsides; although it protects your vulnerabilities, your softer parts, it hurts and damages those who bump up against it.

We all know that masculinity is at the root of the homophobic culture in our high school; it’s a convenient protection against “the other”, a rallying point of microaggressions, because after all, masculinity and gayness are mutually exclusive, right? Ha! Little do you know!

We all know that masculinity is why many of our girls feel objectified. I’ve heard the popular myth that girls always fall for the bad guy, but “no simp” as an approach to dating? Really? What century are we in?

But I also feel for the vulnerability of our boys. Don’t get me wrong. I do not excuse bad behaviour, particularly when it hurts others, but I do want to understand it. Being born with a penis (whatever its size) puts you way ahead in life’s race, but I know it comes with a health warning. We’ve all read the frightening statistics on the incidence of male suicide in the late teens and early twenties – and, unforgivably, this is still even higher for gay men and boys.

We say we are committed to preparing our students for the fast-changing world that awaits outside of ISL’s metaphorical gates where “soft skills” are increasingly valued and important. So how do we encourage our boys to take off their armour and find their place in this world – to shift their focus from being unashamedly masculine, to being unashamedly human in all of its diverse and wonderful facets?

I have no answers, but I’m happy to lead the debate.

John Ivett