Feel Good Inc.

It’s Mindfulness Monday. After scrolling through the countless celebrity-voiced guided meditations on the Calm app, my homeroom teachers begrudgingly select a pre-recorded audio message by LeBron James highlighting the importance of a good night’s rest before “game day”. It’s 8:25 in the morning, and most of us are running on much less than LeBron’s “8 and a half hours” of sleep. Some of my classmates are indifferent, using LeBron’s soothing voice as background noise for a brief power nap. Others are carefully following the basketball star’s instructions as they take deep breaths and attempt to notice the thoughts that are racing through their mind. I’m listening carefully to LeBron’s words – not to follow his instructions, but to listen critically to the messages he is transmitting.

LeBron is talking about the stress he feels as an athlete – something which affects everyone from top-level executives making expensive decisions to high school students struggling to balance their assignments. The way he’s framing the source of his stress, though, is interesting: he deliberately places the blame of his feelings of stress on himself, not the external pressures that he is facing. Not the exploitative billion-dollar basketball industry where his ability to secure sponsorship deals is dependent on his performance in a 48-minute game.

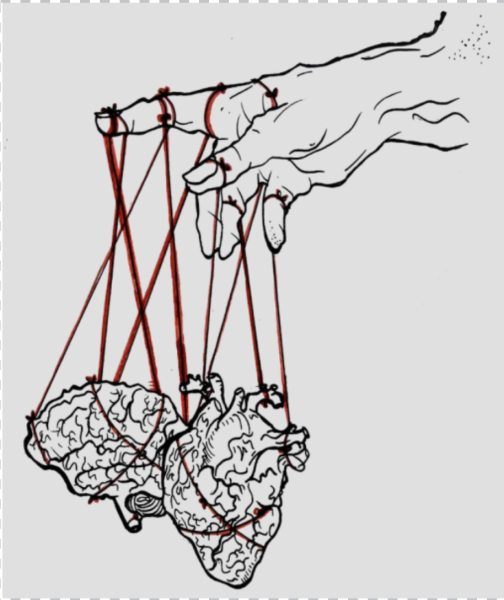

LeBron is likely reading from a script after being offered a lucrative deal by Calm, the app valued at $1 billion which is hosting this speech. Mindfulness is a trillion-dollar industry, and ISL is one of its participants. When something becomes an industry, it becomes a double-edged sword, increasing accessibility but also seeking to justify the conformist messages of the society that it is a part of. The mindfulness industry is no different: its focus on adjusting to certain societal pressures rather than working to liberate oneself from them simply legitimizes the “pull yourself up by your bootstraps” thinking that plagues our modern society.

This individualization of systemic problems is having an impact on students. We are becoming blind to the structural factors responsible for generating our stress: the external pressures to perform well in school to access elite institutions after graduation is a byproduct of our system, and a widespread social movement to dismantle this thinking rather than individuals developing resilience towards these systems is what we need. Simply put, our mental health is painted as apolitical. It shouldn’t be.

At ISL, where we are already part of a privileged, “elite” group, most of our stress does not come from thinking about where the next paycheck comes from, or the ever-pervasive police presence in our neighborhoods. But mindfulness education is slowly being introduced in areas where such systemic issues are a major source of stress for people. Mindfulness, in this form, encourages passivity in face of systems of oppression. This has detrimental effects – Ronald Purser, author of best-selling book McMindfulness argues that “by failing to address collective suffering, and systemic change that might remove it, they rob mindfulness of its real revolutionary potential, reducing it to something banal that keeps people focused on themselves.”

Furthermore, with the civilization and later commercialization of mindfulness comes the removal of its cultural origins. What we’re doing in school (and most other institutions) isn’t even mindfulness. It’s concentration training. Mindfulness is an integral part of Buddhism, with Sati (the original term for mindfulness) being the first step towards reaching enlightenment – a goal for many Buddhists. The original intention for mindfulness is not to make us happier or less stressed for an upcoming test, but rather to change our sense of self. But now, it is being sold as a miracle “cure-all” for everything from weight loss to depression. While the positive effects may be there for some, it is not a one-size-fits-all solution.

I am not arguing that mindfulness (or rather, our neatly packaged version of it) is not helpful. Our individual mindset when in stressful situations determines our actions when trying to resolve it, and taking some time to be aware of certain thoughts further contributing to our stress does make us feel more at ease. Based on my own experience, mindfulness, when done correctly, can pave the way for the much longer journey towards self-actualization. From practicing mindfulness, I am slowly becoming a less judgmental person. I am reacting better under stress. None of this was through a neatly-packaged audio recording from the Calm app blasted through the speakers on a Monday morning, though; it was through discovering the true intentions of the practice and testing out if it worked for me.

I don’t think ISL should stop implementing mindfulness into the social and emotional learning program. Rather, I suggest more transparency as to what mindfulness is so that students could appreciate its original intentions. After informing students about this, it should be an optional exercise. ISL is already taking steps in the right direction with meditation and reflection rooms in the North Campus. This case-by-case approach, in conjunction with an awareness of the structural factors that are contributing to students’ stress (exams, social pressures, university preparation) could be incredibly powerful. With a move towards qualitative evaluation rather than grades for year 7 students’ first semesters, we are once again heading in the right direction.

Ultimately, we need to examine mindfulness with a critical eye but not abandon it altogether: it can be helpful for some. With that being said, I’m going to take five minutes to focus on my breathing and notice whatever thoughts arise.

I’m Tanvi, Editor-in-Chief of The High. I’m The High’s resident pretentious music snob™, which is a title that I take very seriously. When...