Man Up

Five years ago, I had my first experience supporting a friend struggling with suicidal ideation. After talking for a while, he told me to change the subject. “You’re making me cry,” he said.

“What’s wrong with that?” I asked. “I’m not a girl,” he responded. That same boy recently turned sixteen. However, not all are that lucky. Nearly 16 men die of suicide for every 100’000 people across Switzerland. Now, more than ever, it is vital that we as a society support boys in speaking out about their mental health, as the expectations and traditional gender roles society places on men play a significant role in explaining why men are far less likely to discuss or seek help for their mental health issues

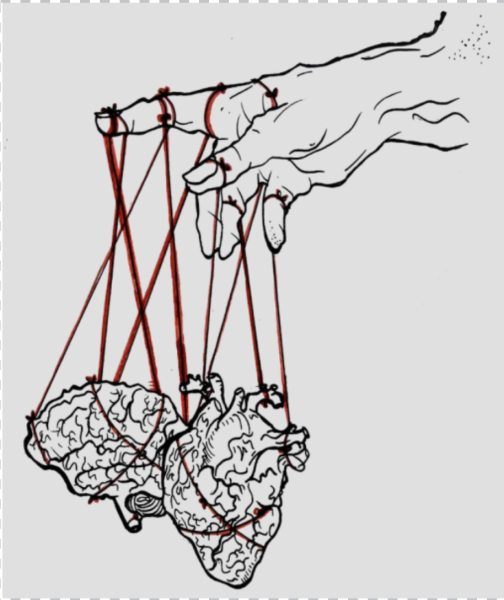

However, it is essential to understand the damage stereotypes and expectations render men to allow those in need to seek help. All too often, men are expected to be the sole or primary stipendiary for their dependents, and while this isn’t inherently a bad thing, failure to adhere to societal norms creates conflict with one’s self-image and esteem. Research suggests that men who are unable to speak about their issues are far less likely to recognize the problems within their mental health and, in turn, reduce the chance of gaining support.

It’s astounding how little research has been done on how men and boys deal with work and personal strain. Male psychological and emotional diseases have a similar lack of research. The fact that this history has been so inadequately recorded is a point of contention.

Some believe that men are simply less susceptible than women to be affected by mood disorders as females are inherently more susceptible to such issues. Women tend to be more likely than men to experience depression and anxiety disorders, as indicated by increased rates of consultations, diagnoses, and psychotropic medication prescriptions. This has been the case since the 1950s, with recent statistics indicating that women are approximately twice as likely to develop and experience psychological disorders

While mental health problems and disorders tend to be universal across genders, seeking help is highly stigmatized. Research suggests that the statistical landscape reveals only part of the story. We know that men are six times more likely to commit suicide. This pattern can be directly traced to data suggesting it has been the case since the beginning of the twentieth century. Often linked to suicide, substance abuse is also more prevalent in males, who are more than twice as likely as women to become dependent on alcohol. This characteristic is well-established, and it has been a recurring feature in studies of general practice morbidity since the late 1950s.

“Alone we can do so little; together we can do so much.” – Helen Keller.

Mainstream gender expectations discourage men to view their emotional well-being as important: their pain is only seen as legitimate if it has a physical source. The concept of care for psychological ailments continues to be one that poses additional challenges to machismo, made more complicated by the reality that when men seek medical help, it is only because they present with somatic or psychosomatic symptoms. Therefore, it is highly likely that male depression and anxiety disorders cases are under-diagnosed. Family doctors in the 1950s noted that women tended to present with sadness, anxiety, lack of motivation, and despair (which are easy to recognize for the most part). In contrast, men were far more likely to present with somatic symptoms, including a variety of ill-defined conditions affecting the stomach, digestion, sleep, and general well-being.

Anyone can hit a crisis point. Fortunately, non-governmental organizations (NGOs) such as Mind, Men’s Health Forum (MHF), and Campaign Against Living Miserably (CALM) aim to provide advice and support to empower anyone experiencing a mental health problem, as well as a campaign to improve services, raise awareness and promote understanding. They provide confidential services such as helplines and webchats, as well as support for those bereaved by suicide. Furthermore, universities such as Stanford run initiatives to investigate the power the media has to make a transformational impact on mental health, when used accurately, safely, and in ethical, developmentally appropriate ways in order to improve the impact of the media on mental health and enhance the prosocial safe use of media in multiple forms. Together, we can help to reduce stigma.

Hi, I'm Esme, and I'm in year twelve. I both write and illustrate for the High. In both, I try to provide an opinion on STEM, politics and popular culture....